Japan’s Greatest Success Story - The Ambition and Aesthetics Behind Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the Tenkachaya Stone Lantern

Share

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598) rose from humble origins to become one of Japan’s most powerful historical figures. Born into a peasant family, he served under Oda Nobunaga, demonstrated remarkable talent, and ultimately rose to the title of Kampaku (Imperial Regent) and Daijō-daijin (Chancellor), becoming the de facto ruler of Japan.

His life is often hailed as Japan’s greatest success story. However, behind this brilliance lies a more complex tale — a man who indulged in extravagant displays of authority, clashed with cultural figures, and showed ruthless tendencies in his later years. The Tenkachaya Stone Lantern, a garden ornament inspired by a teahouse Hideyoshi is said to have visited, reflects both his aesthetic ambition and his personality.

Note: While the Osaka neighborhood is pronounced "Tengachaya," the lantern is read as "Tenkachaya."

The Tea Aesthetic — Clash Between Hideyoshi and Sen no Rikyu

Sen no Rikyu, originally a merchant from the port town of Sakai, gained influence through his deep knowledge of tea utensils and his discerning eye for quality. He became a leading figure in the world of tea and was appointed tea master by Hideyoshi. Initially, Hideyoshi admired Rikyu’s refined sense of beauty and adopted his values. However, as Rikyu’s influence in political and cultural circles grew, Hideyoshi began to resent the authority of a merchant-turned-cultural icon.

Rikyu promoted a tea ceremony rooted in wabi-sabi — the aesthetic of simplicity, imperfection, and quiet restraint. Hideyoshi, on the other hand, sought tea as a stage for power. His golden tearoom, lavish utensils, and large-scale tea gatherings stood in stark contrast to Rikyu’s philosophy. Their conflicting worldviews eventually escalated, and in 1591, Hideyoshi ordered Rikyu to commit seppuku (ritual suicide).

This event symbolizes the enduring tension between power and aesthetics, between external grandeur and internal harmony.

The Tenkachaya Stone Lantern — Stonework Inspired by a Teahouse

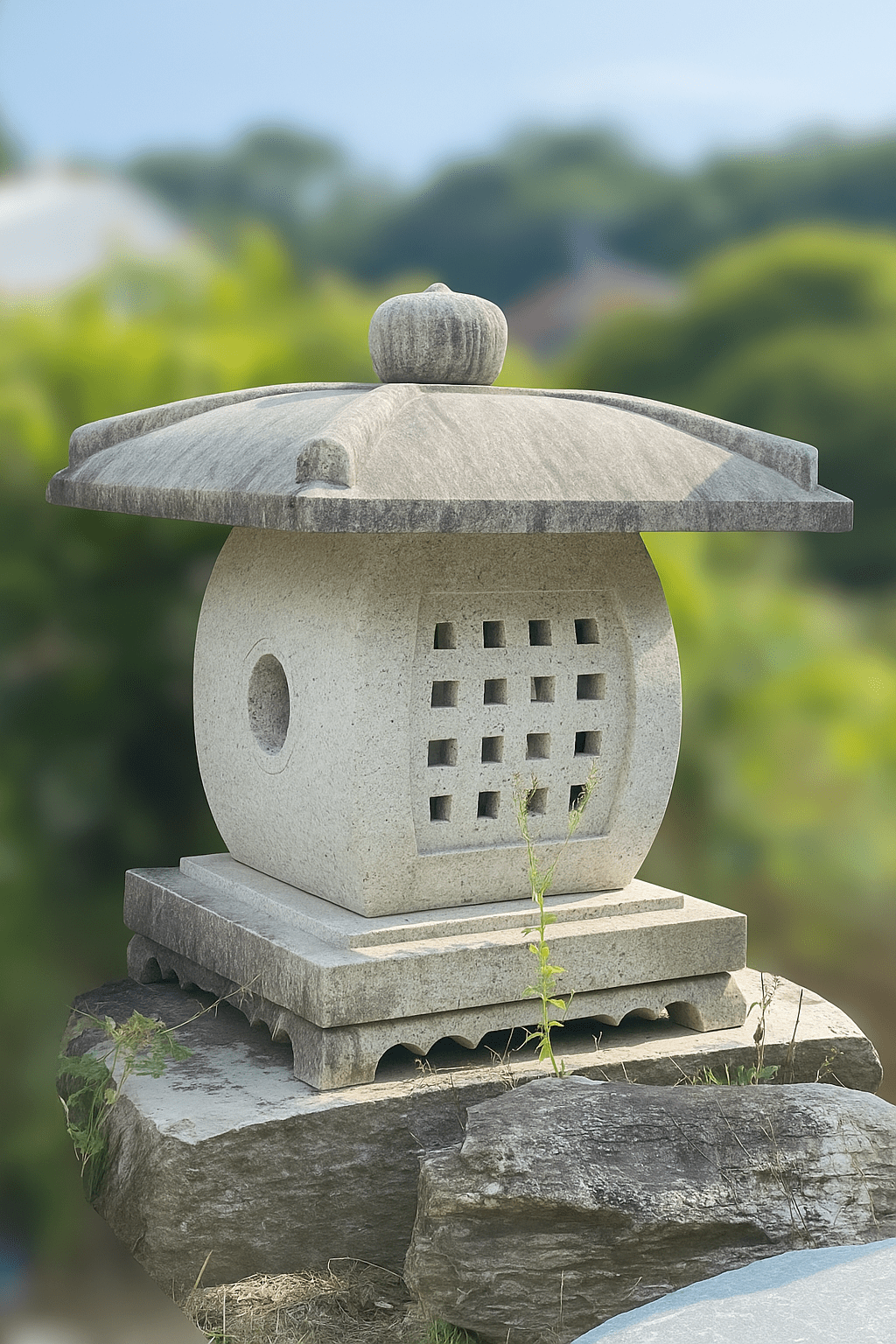

The Tenkachaya Stone Lantern draws inspiration from a teahouse visited by Hideyoshi. Its soft, sweeping rooflines, lattice fire chamber, and rounded column form a cohesive design. Far from being just a light source, it represents the theatricality and formality of tea ceremonies as performed in Hideyoshi’s style.

While Rikyu emphasized invisible beauty, this lantern embodies visible beauty — an aesthetic meant to impress and command attention. In this way, it reflects Hideyoshi’s desire to blend culture with power, elegance with dominance.

The Rise and Solitude of a Self-Made Man

As he consolidated power, Hideyoshi grew more authoritarian. In one infamous episode, he ordered the forced suicide of his adopted heir, Hidetsugu, and the execution of his entire family. This act of cruelty stained his legacy and foreshadowed the collapse of the Toyotomi clan after his death.

His later years were marked by ambition and contradiction. He launched military campaigns in Korea that drained resources and morale. Meanwhile, he continued to act as a patron of the arts, constructing grand castles, sponsoring festivals, and preserving rituals — all to enhance the spectacle of rule.

Symbol of Ambition and Aesthetic Philosophy

The Tenkachaya Stone Lantern quietly reflects the complexity of Hideyoshi’s legacy. For Sen no Rikyu, the tea ceremony was a realm of introspection and quietude. For Hideyoshi, it was a stage to demonstrate hierarchy and glory.

This lantern does not express the subtlety of wabi-cha. Rather, it is a stone embodiment of showmanship and magnificence. When placed in a modern Japanese garden or overseas Zen retreat, it becomes more than decoration — it becomes a vessel of history.

The Legacy of Sen no Rikyu and the Continuing Lineage of the Three Sen Families

Although Sen no Rikyu was forced to take his own life, his teachings endured. His grandson, Sen Sōtan, played a central role in reviving the tea tradition, leading to the formation of the three principal tea schools of Kyoto: Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushanokōjisenke.

These three houses, collectively known as the San-Senke, remain active today and have spread Japanese tea ceremony practices around the world. All three consider Sen no Rikyu their spiritual founder. His ideals of harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility continue to inform their approach to tea and aesthetics.

In contrast, Hideyoshi’s vision of tea was momentary and magnificent — a flash of brilliance from Japan’s greatest self-made man. The Tenkachaya Lantern stands as a testament to this duality: ambition carved in stone, set against a backdrop of quiet contemplation.

Explore the Tenkachaya Stone Lantern