The Taj Mahal - A Love Story Carved in Stone

Share

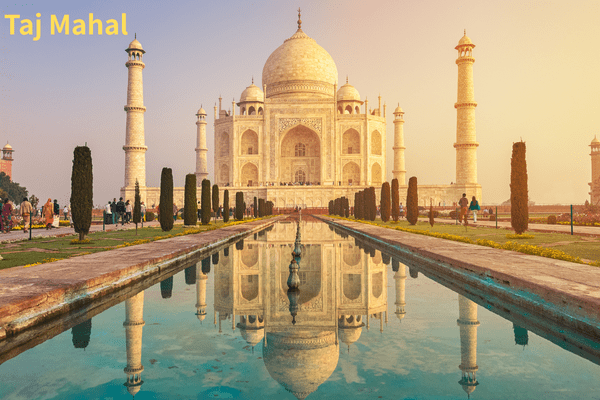

When Mumtaz Mahal died in 1631, Shah Jahan, the 5th Mughal emperor, vowed that her memory would never dim. The Taj Mahal is that vow made visible—grief translated into geometry, devotion rendered in light-holding marble, and a garden planned so that love appears perfectly symmetrical from every human point of view.

How Love Became Architecture

- Era: 17th-century Mughal Empire (Patron: the 5th Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan, r. 1628–1658)

- Promise: Build a mausoleum worthy of Mumtaz—pure, radiant, and enduring.

- Place: Agra, on the right bank of the Yamuna River, where reflections double what the heart sees.

- People: Mughal master builders, carvers, inlay artists, calligraphers—thousands of highly specialized hands sustaining a single grief.

- Plan: A charbagh (four-part Mughal garden) and a perfectly balanced composition—mosque to the west, jawab to the east, minarets guarding each corner.

- Making: Stone was quarried and ferried along the Yamuna; brick-and-lime cores were sheathed in marble and sandstone; precision setting delivered the lace-like clarity of the details.

Court & Consorts — “a single mourning” that set the order

The Mughal court permitted polygyny among emperors and nobles, and Shah Jahan likewise had other wives and consorts (e.g., Kandahari Begum; Izz-un-Nissa Begum, known as Akbarabadi Mahal). Yet the great majority of his children were born to Mumtaz Mahal (Arjumand Banu Begum), his chief consort and political partner. After her death in 1631, the emperor withdrew into prolonged private mourning while his eldest daughter, Jahanara Begum, served as Padshah Begum and ran court affairs.

In 1632, construction began on a mausoleum dedicated to Mumtaz alone. The exceptional rites of mourning and the state-scale memorial effort centered exclusively on her; later, Shah Jahan himself would be laid to rest at her side. In the architecture of grief, this singular focus reveals both a private devotion and the dynasty’s sense of legitimacy through the mother of its princes.

At a glance: UNESCO 1983 (List ID 252) ・ Visitors ~6.8M/yr

World Heritage Facts & Visitor Numbers

| Item | Detail |

|---|---|

| UNESCO inscription | 1983 (Criterion i — masterpiece of human creative genius) |

| Period | Mughal Empire, 17th century (construction c. 1632–1653; patron: the 5th Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan) |

| Location | Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India (right bank of the Yamuna; Mughal garden ~17 ha) |

| Management | Archaeological Survey of India (ASI); within the Taj Trapezium Zone (environmental buffer) |

| Annual visitors (FY 2023–24) | 6.10 million domestic + 0.68 million foreign ≈ 6.78 million total |

Materials of Devotion (at a glance)

| Part / Use | Material | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Main mausoleum (facades, dome, interior panels) | White marble (Makrana) | Fine-grained, slightly translucent; takes ultra-crisp carving and jewel-like inlay (pietra dura). |

| Ancillary buildings (mosque, jawab, gateways) | Red sandstone | Warm chromatic frame that intensifies the tomb’s whiteness. |

| Platform & terrace | Marble cladding over sandstone/brick cores | Visual lightness above; hidden structural mass beneath. |

| Wall cores | Fired brick with lime mortar | Efficient cores sheathed in stone for strength and finish. |

| Inlay decoration (pietra dura) | Carnelian, jasper, agate, lapis, etc. | Botanical motifs and script—love drawn in minerals. |

| Calligraphy outlines | Dark stone (black marble / basalt, etc.) | Materials vary in records; the function is contrast and legibility. |

| Finial & fittings | Metal (copper alloy / bronze) | Symbolic crown to the dome; ceremonial finish to the skyline. |

| Granite (granite) | — | Not used as a primary visible or structural material. |

Why Marble, Not Granite?

Makrana marble is slightly translucent and accepts razor-fine carving and inlay. Granite, while harder, reads optically heavier and is less suited to the lace-like luminosity the Taj requires. Choosing marble allowed love to appear as light, not mass.

| Stone | Look / Use | Workability |

|---|---|---|

| Makrana Marble | Translucent; ideal for fine inlay & sculpture | Carves very fine; accepts intricate pietra dura |

| India Granite Black | Deep tone, high durability (modern gardens) | Excellent for plinths, steps, copings; low translucence |

Related Stone Today — India Granite Black Stone (we carry this)

Note: Granite is not a primary material of the Taj Mahal, but for today’s gardens and architecture we also work with India Granite Black Stone for its deep tone, durability, and low maintenance. Paired with white marble, it creates a balanced, timeless contrast.

- Typical uses: plinths and bases for lanterns/statues, steps & copings, edging, table tops, name stones.

- Finishes: polished (high sheen), honed (matte), flamed/bush-hammered (textured for traction).

- Care: Very durable with low water uptake; avoid standing water on polished surfaces in freeze–thaw climates.

Explore our India Granite Black Stone Products

Design Language of Devotion

- Symmetry with mercy: Minarets tilt outward slightly so, if ever they failed, they would fall away from the tomb.

- Optical care: Qur’anic calligraphy widens with height so it reads evenly from the ground—architecture that meets the human eye.

- The marble that “changes colour”: At dawn it can blush pink; by day it reads cool white; by moonlight it glows warm—light playing within fine-grained marble and Agra’s sky.

- Garden of reunion: The charbagh evokes paradise—the lovers’ reunion beyond time, mirrored in water.

Legends & Lore — Black Taj (Myth vs Fact)

Myth: Shah Jahan, the 5th Mughal emperor, planned a twin mausoleum in black marble across the Yamuna (Mehtab Bagh).

What records & digs say: ASI excavations at Mehtab Bagh revealed a carefully engineered Mughal garden with waterworks—no foundations for a second Taj. Today the site frames the tomb in reflection.

Another long-told tale: That craftsmen’s hands were cut to prevent any rival to the Taj’s beauty. Historians find no contemporary evidence; the region’s craft traditions flourished long after.

Care, Time, and the Color of Memory

Pollution and time can dull marble’s glow. Conservators use gentle, reversible methods (e.g., traditional mud-packs) so the stone can keep carrying light—because the story it holds still matters.

Brief Timeline

| Year | Moment |

|---|---|

| 1631 | Death of Mumtaz Mahal; the 5th Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan’s vow. |

| 1632 | Construction begins at Agra under the Mughal court. |

| 1648 | Main mausoleum substantially complete; finishing works continue. |

| 1653 | Complex completed—love given an earthly address. |

| 1983 | Inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (Criterion i). |

FAQ

Q. Is granite used in the Taj Mahal?

A. Not as a primary visible or structural material. The monument’s signature is white marble (with sandstone, brick cores, lime mortar, and mineral inlays). Records do not identify granite as a main material.

Q. When do the marble colours look most dramatic?

A. Sunrise and full-moon nights show the strongest shifts; midday reveals the purest white.

Hand-Carved Stone Lanterns (Granite & Marble) ・ Gorinto ・ India Granite Black Stone Accessories ・ Shipping ・ FAQ

Last updated: 2025-08-26 (JST)