Ukiyo-e and Stone Lanterns Vol.2 Utagawa Hiroshige

Share

Utagawa Hiroshige — The Landscape Print Master and What Came After

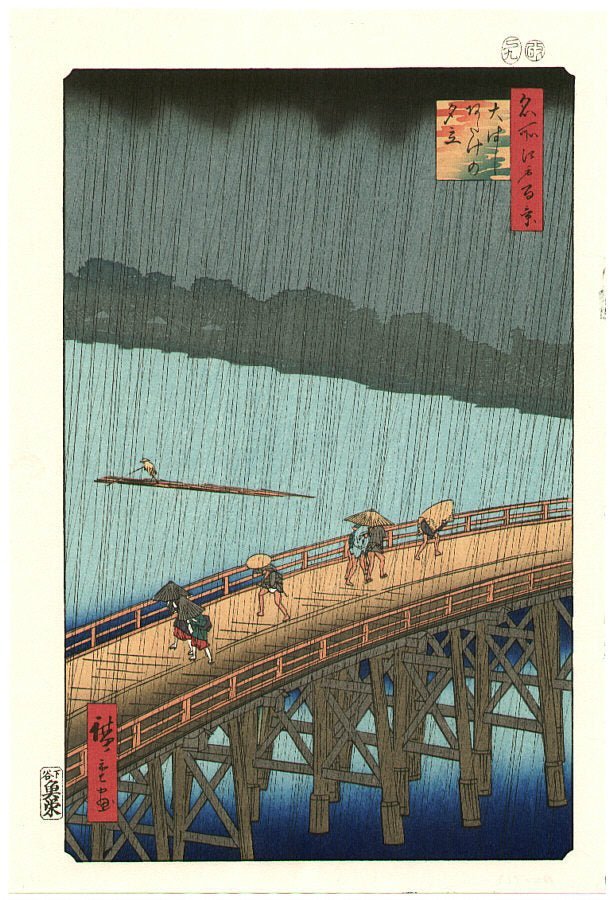

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) was one of the leading figures of Japanese ukiyo-e, elevating landscape prints known as meisho-e (“pictures of famous places”) into a popular culture that ordinary people could enjoy and collect. His series The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Tokyo) captured the seasons, weather, travel, and scenes of daily life with lyrical color and bold composition. In Hiroshige’s landscapes, stone lanterns often appear as part of the roadsides and shrine or temple precincts of Edo (Tokyo). For the people of the time, these lanterns symbolized places of faith and formed part of the everyday scenery that lined paths and courtyards. Such details show that Hiroshige went beyond simple “guidebook pictures,” faithfully inscribing the atmosphere and lived reality of his age.

Key Works at a Glance

- The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido — travel, roads, ferries, post towns, and the flow of people.

- One Hundred Famous Views of Edo — an urban anthology of bridges, rivers, shrines, and streetscapes, painted in the final years of Hiroshige’s life.

- Stone Lantern Motifs — In several prints, especially shrine and temple scenes, Hiroshige depicted ishidoro (stone lanterns). Notable examples include Kameido Tenjin Shrine Grounds and Asakusa Kinryūzan, where rows of granite lanterns flank the paths. These lanterns were not decorative details alone but cultural symbols, linking worship, everyday life, and landscape design in Edo Japan.

- Hiroshige’s Color Language — atmospheric blues and gradations (bokashi) that shaped global taste and influenced Western artists.

Hiroshige’s Name Through Five Generations

After the first Hiroshige passed away, the name continued to the fifth generation. This lineage helps readers situate Hiroshige within the broader arc of ukiyo-e history.

| Generation | Name / Birth Name | Lived | Succession & Position | Activity & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Utagawa Hiroshige (Andō Tokutarō) | 1797–1858 | Master of the Utagawa school | Established landscape print idiom; Tokaido and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. |

| Second | Hiroshige II (Shigenobu → later Kisai Risshō) | 1826–1869 | Disciple and son-in-law of the first | Followed the first Hiroshige’s style closely; collaborated on late works; later engaged in export crafts. |

| Third | Hiroshige III (Gotō Torakichi → Shigemasa) | 1842–1894 | Married Hiroshige I’s daughter after II’s divorce | Produced kaika-e (modernization prints) and new city views during the late 19th century. |

| Fourth | Hiroshige IV (Kikuchi Kiichirō) | 1849–1925 | From the school; succession by connection | Carried the name into the modern era; also active in calligraphy and literature. |

| Fifth | Hiroshige V (Kikuchi Torazō) | 1890–1967 | Son of the fourth | Maintained the family name through the 20th century, when print demand was shrinking. |

Why Ukiyo-e Eventually Ended Its Role

By the late 19th century, as the samurai era ended and Japan modernized, photography spread rapidly. With unmatched realism and speed, photographs took over many practical uses that prints once served — travel records, city views, and personal portraits. At the same time, new mass media such as lithography, newspapers, and magazines rose to prominence. Step by step, ukiyo-e ended its role as the frontline medium of everyday imagery.

Overseas Reappraisal — Japonisme

While domestic demand faded, ukiyo-e crossed the seas and electrified Europe. Collectors, critics, and painters embraced its flat color planes, cropping, and asymmetry. Impressionists such as Monet and Van Gogh drew direct inspiration, and ukiyo-e helped reset Western ideas about composition, color, and perspective.

From Ukiyo-e to Manga — A Living Line

In Japan, many of the core sensibilities of ukiyo-e — depicting everyday life, compressing narrative into a single frame, and guiding the eye through visual rhythm — re-blossomed in manga and animation. Hiroshige’s legacy thus travels along three currents: decline at home as media changed, reappraisal abroad, and a quiet transformation into today’s popular culture.

Quick Facts

- Discipline: Ukiyo-e (woodblock prints), landscape focus

- Signature Strengths: atmospheric color (bokashi), seasonal mood, travel narratives

- Stone Lanterns: recurring motifs in shrine and temple views, symbolizing devotion and garden culture

- Global Impact: Pivotal to Japonisme; influenced Impressionism and modern design

- Continuity: Name carried to the fifth generation; role of ukiyo-e shifted as photography and print media expanded

FAQ

What made Hiroshige different from Hokusai?

Hokusai dramatized movement and bold form; Hiroshige emphasized atmosphere, color gradation, and the poetics of place. Together they defined the golden age of landscape ukiyo-e.

Did photography “kill” ukiyo-e?

Photography delivered realism and speed, and alongside newspapers and lithography, it displaced ukiyo-e’s everyday functions. It is more precise to say ukiyo-e ended its role as the primary popular image medium.

Did Hiroshige depict stone lanterns?

Yes. In prints such as Kameido Tenjin Shrine Grounds and Asakusa Kinryūzan, stone lanterns appear prominently. They reflect Edo-period faith, daily pathways, and garden aesthetics.

How is ukiyo-e connected to manga?

Ukiyo-e’s storytelling in single frames, everyday subjects, and visual pacing echo in modern manga and animation.

A Symbol of Zen - The Tranquil Heart of the Japanese Garden